For those interested in the urban housing crisis, I recently published What Really Drives Housing Prices? on my personal blog. There I write and share analysis on subject matter that I find deeply important but off-topic for this newsletter.

Now, for your (ir)regularly scheduled broadcast…

Though densely interdependent, building technology and building products are two distinct activities.

Technology-building—the invention of new technologies—is a higher risk and slower activity than product-building. It requires unusually patient capital. For this reason it tends to happen in research labs funded by large governmental, academic, or corporate institutions.

You can trace most technologies back to these institutional research labs.

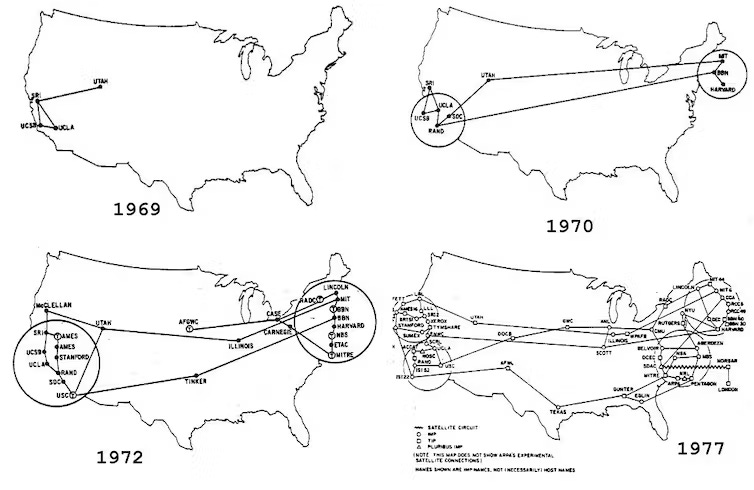

The US government is an especially potent generator of new technology. Government research labs like DARPA developed GPS, cellular communication, touch screens, drones, accelerometers, the first “Street View”, and funded the development of mRNA vaccines. We also have DARPA to thank for the internet.1

University-affiliated labs have also proven bountiful. Computer vision, e-ink, e-mail, and many other technologies were developed at MIT. Stanford Research Institute (SRI) produced the computer mouse, the inkjet printer, and the voice interface technology used in Apple’s Siri. The first AR head-mounted display system was developed at Harvard in the 1960’s. Larry Page and Sergey Brin developed PageRank at Stanford University before founding Google. The first text-to-image diffusion model was introduced by researchers at the University of Toronto in 2015.

We have corporate research labs to thank for many of the fundamental technologies of the digital era. Bell Labs developed the first transistors, lasers, charged-coupled devices, and solar cells as well as Unix and the C programming language.2 RCA Laboratories invented LCD displays, electron microscopes, and the first color television. Today, big tech companies like Google, Meta, Microsoft and Apple have their own internal labs for this kind of basic research.3

This pattern is likely to continue into the future, with independent non-profit labs playing a prominent role. It’s not an accident that OpenAI built the large language model underlying ChatGPT as an independent non-profit research lab before transitioning to a for-profit model in 2019. Few people know more about the strengths of the research lab model for building groundbreaking technologies than my friend Ben Reinhardt. He recently started Speculative Technologies, a non-profit research lab focused on materials and manufacturing, modeled after DARPA.4

Basic research labs are well-suited to building technology in part because they are ergodic — they generally get to fail as many times as necessary as they explore the entire search-space. If there’s gold to be struck, they’ll eventually strike it.

As a general rule, startups don’t build technology. Startups apply technology to build products that address a user need in the market. Neither Zoom nor Skype invented videotelephony or the image compression algorithms that make it possible, yet Zoom applied these technologies to become critical infrastructure for remote work around the world. Uber and Lyft didn’t invent GPS or mobile technology, yet they effectively harnessed these technologies to birth the multi-billion-dollar ride-sharing industry. Startups are usually better positioned to adapt, refine, and assemble existing technology rather than fundamentally build it.5

For example, the current explosion of AI startups isn’t driven by new companies building AI, it’s driven by companies searching for novel ways to apply this new technology through products. Many are little more than wrappers on ChatGPT’s API—and that’s to be expected!

This is not due to any lack of ingenuity or creativity among startups. It’s a direct consequence of the very nature of a startup's structure, resources, and goals.

The capacity of startups to create new technology is constrained by their dependence on venture capital, which demands a swift path to profitability and tolerates less technological uncertainty. The demand for swift and dramatic return by VCs should not be underestimated—they are competing with the ROI of every other asset class for the capital provided by their LPs. Unlike research labs, startups don’t have the luxury of patient capital.

This limited runway means that startups are non-ergodic—they get a limited number of times at bat before they cease to exist. This high-stakes environment creates very different developmental dynamics from those of research labs, where ongoing failure is accepted as a part of the process.

In light of these constraints (which come hand-in-hand with the upside of value capture), startups must limit their exposure to risk. Where research labs assume technical risk, startups assume market risk. It makes no sense for anyone to assume both. A healthy tech ecosystem distributes these risks so that no single actor takes on too much.6

Startups need to understand their role in this ecosystem in order to fulfill it successfully. Many operate as if they’re developing new technologies in research labs instead of new products inside a startup (they just do it faster). In my next post I’ll explore the implications of this problem and offer an alternative development model that I believe is better adapted to the needs and constraints of startups and product teams.

See Mariana Mazzucato’s The Entrepreneurial State for more on the government’s role in technological innovation.

See Jon Gertner’s The Idea Factory: Bell Labs and the Great Age of American Innovation for the incredible history of Bell Labs. It’s worth mentioning that this lab operated under heavy regulation by the US government in exchange for AT&T’s monopoly status. By law, their inventions were made available to competitors.

However, as my friend and Flux collaborator Ade Oshineye pointed out to me, even though these labs enjoy the capital of Big Tech, the demands of shareholder ownership are comparable to those of VCs on startups.

Ben also explores the different dynamics of research labs and startups in his excellent post, When should an idea that smells like research be a startup?

Since technology progresses through a process of combinatorial evolution (see Brian Arthur’s The Nature of Technology), and products are often the novel combination of different technologies, the line between technology and product can be admittedly blurry. However, there’s instrumental value in distinguishing the two. In most instances it would benefit founders to embrace the idea that startups are for building products, as this is a superior mental model for achieving their goals.

VCs are also keenly aware of the additional risk they take on by funding a startup that’s trying to build a new technology. As Jerry Neumann writes, “Technical risk is horrible for returns, so VCs do not take technical risk…VCs have always waited until the technical risk was mitigated…Market risk, on the other hand, is directly correlated to VC returns.”

Happy to see Mazzacuto given a shout out here. Another good economics book on this is Bit Tyrants by Rob Larson.