One of the most important exercises I run with product teams is about shifting their approach to epistemic hygiene—is that claim we’re making decisions based on a fact, an opinion, or a guess?

There’s lots of load-bearing claims in the process of product development. Some are explicit, many are assumed.

“Our users care a lot about the author behind the content they consume.”

“The market for personalized healthcare experiences is enormous.”

“Our organization’s leadership values measurable climate impact.”

“This new technology will make just in-time interfaces feasible.”

These claims are memetic, flying around documents and meetings in a frenetic game of telephone.

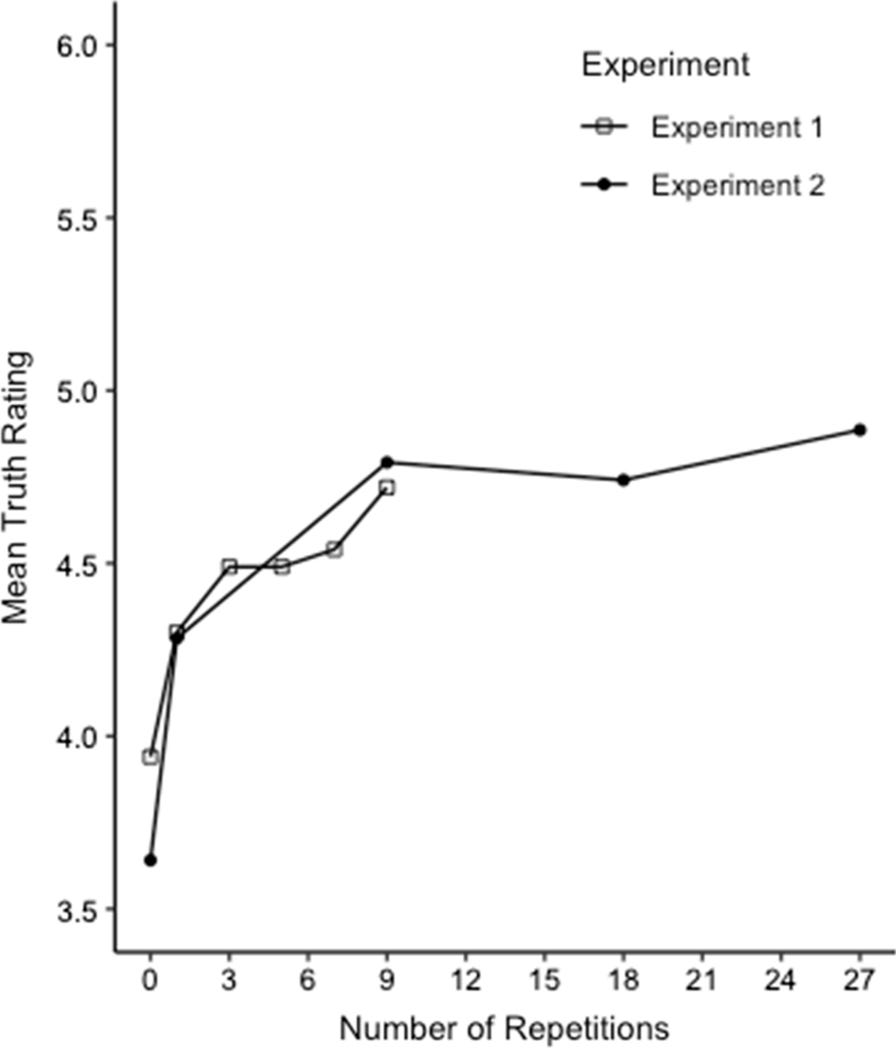

As these claims are repeated, they quickly gain the weight of truth among team members.

While repetition from multiple internal sources might make a claim feel true, repetition is a weak basis for critical decision making.

Often these claims have no empirical origin. The originator of the claim might know this (and he or she might assume everyone else knows this), but elsewhere on the team decisions are being made as if that claim were rock solid.

I like using structured exercises with client teams to collectively elucidate, map, and grade the epistemic status of these load-bearing claims, but I’ve often found a well-placed dumb question can sometimes spark a necessary review of a claim’s provenance almost as well.1

This might sound like:

“What is that decision based on?”

or

“Interesting, how do we know that?”

Simply nudging team members to attach an epistemic status to claims in group contexts can reveal misalignment. Shorthands are useful.2

Fact: A claim grounded in robust qualitative and/or quantitative empirical data

Opinion: A claim grounded in limited data, personal experience, anecdote, or strong hunches.

Guess: A claim that exists usually because a claim needed to exist in order to move forward.

In the chaos of product development, basic operating heuristics tend to flatten all claims down to the same epistemic status (usually as a ‘fact’) in order to move forward. When these assumptions are made legible by grading the claim as a fact, opinion, or guess, it quickly becomes clear that one subset of team members was operating on the premise that a claim was fact while another knew it to be an educated guess. Or, we discover that everyone thought it was a fact because everyone assumed someone else had hard data, when if fact no one did.

Sometimes these misalignments follow the fault lines of seniority. An opinion from someone senior is interpreted as a fact by someone junior by virtue of their authority, or a guess by someone junior is transmitted as fact to senior team members in order for a middleman to save face.

The value is not in getting the team to agree that a particular claim is “a fact” or “an opinion,” but in identify precisely where there is a lack of agreement in the first place, and why. Perhaps some of the team hasn’t seen the research that others have—or perhaps there’s no research at all. In this case, an applied bit of empirical handy work (whether it’s rigorous research or simply a few key conversations) can provide nuance and confidence to the current path or avert a crisis before it hits if the leading assumption turns out to be false.

The earlier a team can practice good epistemic hygiene, the better. Once an unsubstantiated claim has taken on the veneer of truth and especially once critical decisions have been made on its basis, it becomes painful to course correct. Investments have been made, promotions planned, stakeholders appeased, and no one wants to lose face. Even in earlier-stage companies where these politics are less pronounced, the same mindset can still infect the product development process.

Not every decision must be based on hard data,3 and 100% certainty is an illusion whenever you’re building something new, but taking a periodic moment for epistemic hygiene is a low-cost, high-impact way to keep a team moving towards its goals.

Being a naive outsider makes this easier, as I benefit from the assumption that I’m just trying to understand what’s going on (which is also true). From someone inside the team, these questions can be perceived as obstructionist or even threatening depending on team culture. In this case, more attention to gentle framing or broaching these questions in 1:1s or smaller forums first may be warranted.

Try to not get bogged down in the lines between facts, opinions, and guesses. Their precise distinctions are unimportant (you could just as as easily call them “high confidence,” “medium confidence,” and “low confidence”).

In the exercises I facilitate, the next step after epistemic grading is systematically determining whether the downstream decisions based on these claims are indeed critical enough to warrant further inspection. Velocity matters too!

I worked with a research manager at Microsoft, a place known for hiring over confident product managers who skillfully weave opinion into seemingly factual arguments, who liked this well placed dumb question,

“What makes you so sure?”

Often times when he knew he had at least some empirical evidence that usually dampened their hubris…and enthusiasm. 😏

This is awesome @Kasey. Ironically, I wrote something along similar lines this week. I touched on the network effect and zero-knowlege proofs - a web3 / blockchain solution that's gaining steam. More here if you're interested - https://mirror.xyz/oriongrowth.eth/1GXMYA-Gbgm-S_U8Du41zZ4DoZ9XeTqXlAhegHzN9wk Thx for sharing Epistemic Hygiene.